nutmeg: a decolonised history

from Indonesia’s Banda Islands to holiday tables, nutmeg's journey reveals hidden narratives of power and resistance

In the winter of 2021, mad with Omicron-induced cabin fever, I decided to make cookie boxes for my friends. I’ve never done this before or since, but in that miserable time I wanted to recreate what I missed most about the holiday season. I didn’t grow up with snow, or crackling fires, or festive decorations; it was the sweet scent of spices wafting from the kitchen, promising warmth and nourishment and togetherness, that gave the holidays their magic.

Like ornaments and fairy lights, nutmeg lives forgotten in most cabinets until the winter, when it re-emerges to dust our eggnogs and flavour our spiced cookies. We reach for it instinctively during these celebrations, this spice that has become so entwined with European winter traditions that we rarely pause to consider its native home—or question how a tropical seed became essential to a season wholly foreign to its origins.

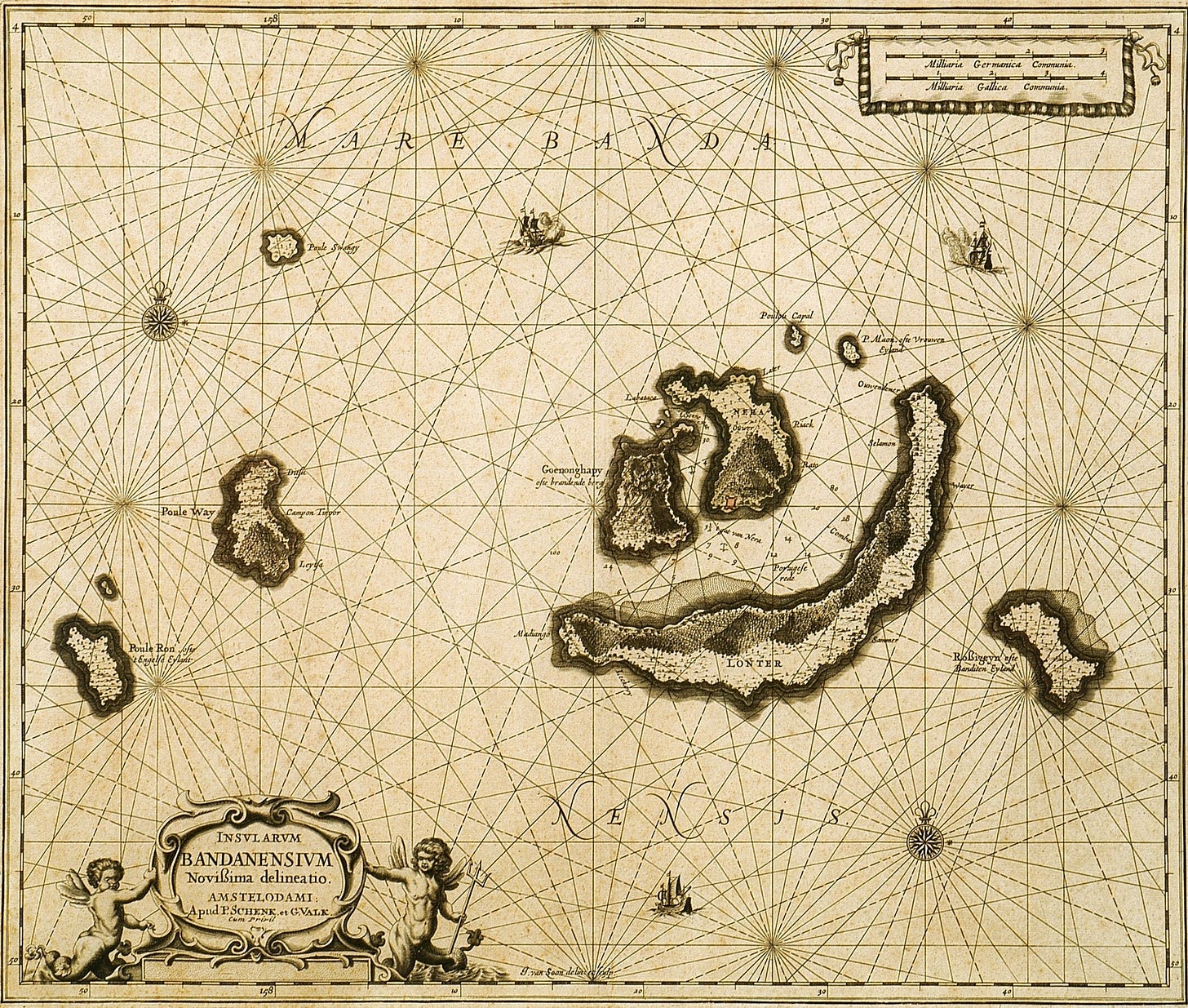

That home is the Banda Islands: a scatter of volcanic peaks rising from a remote stretch of Indonesia's Banda Sea, like seeds carried on the westerlies. Some are little more than steep, rocky pinnacles; others cradle villages between sharp coastlines and dense tropical forests. All are so small they vanish from most maps.

These tiny islands are inextricably linked to another, more familiar piece of land ten thousand miles away. In one of history's most lopsided real estate deals, the Dutch traded the island of Manhattan, a Lenape territory, to English colonists in exchange for dominion over the Bandas. The true prize was a monopoly over the most valuable commodity of the time: not oil or gold, but nutmeg.

There are countless ways to tell the story of nutmeg: through trade routes and colonial histories, through the sterile language of battles and treaties. But I'm most interested in the spaces between these contours—where they begin and end, who they center or push to the margins—the ones that reveal how colonialism's legacy persists in our most mundane rituals. It's here, in the interstitial, that we begin to unravel the threads of empire that still bind our daily lives.

The Spice Islands

“First discovered in 1511 by the Portuguese and later colonised by the British and Dutch” is how most descriptions of the Banda islands begin, as if land only comes into being once sighted through the barrel of a spyglass. Most accounts of nutmeg also begin here, with the bloody history of European conquest over the spice trade, sidelining the Bandanese as tragic bystanders in their own history.

Centering European contact with the Malay Archipelago obscures the fact that this spice had already crossed oceans at least a thousand years before the Europeans arrived. As the world’s sole cultivators of nutmeg, the Bandanese built vast networks that carried their treasure to imperial courts around the world.

"God gave the nutmeg to the Bandas, and to the Bandas alone," said Des Alwi, a Bandanese historian and diplomat who returned to the islands in his latter years to document and advocate for their history and culture. Until the nineteenth century, nutmeg could only be sourced from this tiny unmapped island chain. Here, the unique alchemy of volcanic nutrients, fresh sea winds, and the cool, protective canopy of kenari (wild almond) trees gave birth to one of the most valuable and desired commodities in the world.

Quoted in a 1995 story for the New York Times, Alwi continues: "Look at these trees, how protected they are. Consider the configuration of these islands. They are all of volcanic origin, rising from awesome depths. Only here where they smell the sea. Nowhere else on earth. Small wonder the barbaric Europeans came to us. It finally dawned on them that they ought to enjoy their food."

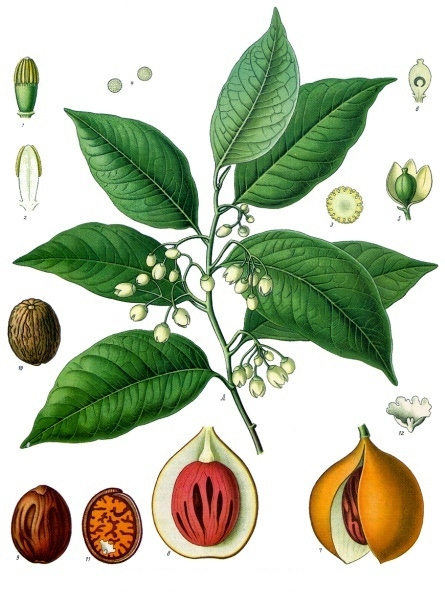

Anatomy of a Nutmeg

Counterintuitively, nutmeg is not a nut. The English name comes from the Latin nux, meaning nut, and muscat, meaning musky. Pala, the name used across the Malay and Indonesian archipelago, comes from the Sanskrit phala, meaning fruit, effect, consequence, reward.

Nutmeg is the fruit of the Myristica fragrans, an evergreen tree. Like gingko, the Myristica fragrans has male and female trees; only the latter bears round, tart fruits that split open when ripe to tease a glimpse of their nested treasures. Peel back the fruit, and you’ll find a glossy brown seed wrapped in a flaming armour of mace, another valuable spice. Crack open the seed to find the final doll: a shy, ash-brown kernel hiding an explosion of sharp, sweet, smoky flavour.

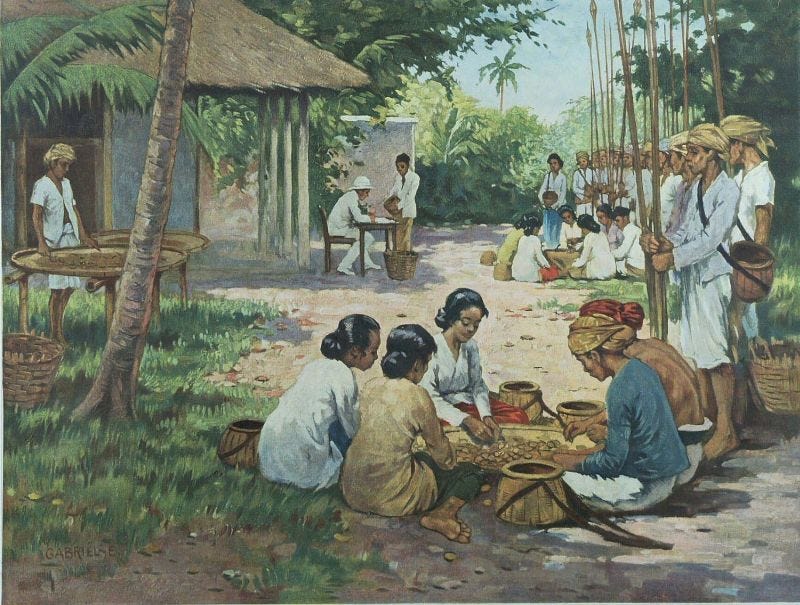

Before the harvest, Bandanese women perform a spiritual cleansing for good fortune. Men coax the fruits from the trees using wicker baskets on long bamboo poles, called gai. The mace is carefully peeled off, pressed flat, and dried in the sun until it turns dull and brittle. The seeds are dried over smoking coals until the nutmeg kernels rattle inside like egg shakers.

Adding to nutmeg’s rarity is its short lifespan. Today, you’re most likely to encounter nutmeg in powdered form, but it’s best to buy it whole. Nutmeg’s aroma burns brightest when grated fresh and fades quickly as its fragrant oils evaporate. (Do yourself a favour and take a whiff of the ground nutmeg in your pantry—if it doesn’t knock you out with the scent of pine, throw it out.)

Masters of the Sea

Three of the larger Banda islands—Banda Besar, Banda Neira, and a still-active volcano—form a voluptuous bikini set. For at least two millennia, boats propelled by monsoon winds passed through Banda’s curvy navel to exchange spices, cloth, sandalwood, precious metals, jewel-bright feathers, and other exotic goods.

In On the Edge of the Banda Zone, anthropologist Roy Ellen explains that trade networks likely blossomed across the region as early as the third millennium BCE.1 Merchants came from islands near and far, from Papua in the west to Java and Malaka in the east. Chinese sources indicate contact with the region from the first millennium BCE. By 300 CE, nutmeg was well established as a prime commodity in Asian maritime trade.

Nutmeg made Banda an unexpected nexus of global trade, but the Bandanese also relied on these networks for survival. Ellen, an ethnobiologist whose research focuses on eastern Indonesia and the Bandas, describes how regional patterns of growing, harvesting, and trading were intricately tied to the local trade ecosystem. Larger islands to the north and east supplied Banda with locally-grown, life-giving staples like sago and rice.

In contrast with neighbouring port communities that waited for merchants to come to them, the Bandanese were spirited navigators who hawked their nutmeg and mace across the archipelago. Portuguese sources from the sixteenth century record Bandanese ships as far as Java and Malaka dealing directly with merchants from across the Indian Ocean.2 Ships from China, India, and Arabia linked the Banda islands to the continental trade paths connecting Asia and Europe.

The Price of Spice

By the first millennium of the common era, nutmeg had travelled the world. The nutmeg’s journey to European markets was long and arduous, gaining more value with each stop until it was worth more than gold. Nutmeg reached Constantinople by the sixth century CE, becoming a favoured luxury among the elite.

Like bread crumbs sprinkled along ancient paths, nutmeg’s ubiquity in spice blends from China to North Africa gives away the secret path that traders kept closely guarded for centuries: first by boat on the eastern monsoon to Malacca and Java, where merchants collected sacks of spices in exchange for silks, ceramics, precious metals, and other raw materials; then back to China, South Asia, and the Arabian Peninsula six months later on the western monsoon; finally by caravan, across the desert to Constantinople, where they sailed to Mediterranean ports in Cairo, Alexandria, Venice, Genoa, and onward to the rest of Europe.

Nutmeg was highly valued in both cooking and medicine. Like eucalyptus oil on a winter morning and camphor on aching joints, nutmeg has a cooling, medicinal warmth. Ancient Hindu texts from the 1st millennium BCE recommend nutmeg for digestion, fevers, headaches, and bad breath. Little wonder that medieval Europeans paid ungodly sums to wear them as amulets against disease and the devil.

By the twelfth century in Europe, nutmeg had attained near-mythical status as a cure-all. St Hildegard of Bingen’s 12th-century medicinal texts included nutmeg in her recipe for “cookies of joy” to treat an imbalance of black bile; nutmeg also appears in Chaucer’s Canterbury tales. Along with its scarcity, nutmeg’s price tag soared on increasingly outlandish claims about its curative properties for ailments ranging from stomach and liver problems to tumours and the bubonic plague.

Perhaps nutmeg’s most magical property was its ability to transform a common merchant into a gentleman of leisure. In Giles Milton’s book Nathanial’s Nutmeg: How One Man’s Courage Changed the Course of History, the author describes how “in the Banda Islands, ten pounds of nutmeg cost less than one English penny. In London, that same spice sold for more than £2.10s. — a mark-up of a staggering 60,000 per cent. A small sackful was enough to set a man up for life, buying him a gabled dwelling in Holborn and a servant to attend to his needs.”3

The Empire Strikes Back

When Portuguese ships first reached the Banda islands in the 1510s, they encountered a prosperous society built on nutmeg cultivation and trade. The islands were governed by orang kaya (rich men), a mercantile oligarchy who ruled collectively over the islands. Unlike neighbouring monarchies that the Europeans could more easily manipulate, the Bandas’ unified governance and natural defenses—rocky coastlines and dense volcanic forests—allowed them to successfully resist Portuguese control for nearly a century.

The Bandanese also played European rivals against each other. When the Dutch East India Company (VOC) arrived in 1599, the orang kaya sought Dutch support against Portuguese incursions.4 However, the VOC’s desire for monopoly over nutmeg, and their willingness to impose it through military power, pushed the Bandanese towards the English. Reliant on trade for food supplies, the Bandanese refused to honour the VOC’s exclusivity contracts, and allied themselves with the English for military protection.

The situation reached a tragic climax in 1621. On a flimsy pretext of Bandanese insurrection, VOC commanders carried out a genocidal campaign, systematically destroying villages, beheading the ruling class, and enslaving their wives and children. When the orang kaya attempted to negotiate new agreements, they were captured and executed.

In seizing control over the spice trade, the Dutch almost entirely eradicated Bandanese society. Of the 15,000 original inhabitants, it’s estimated that only 1,000 survived the initial campaign, with the population further declining to 600 within fifteen years.5 Precious few villagers managed to escape to nearby islands, where they continued rescue and trade operations despite Dutch attempts at suppression.

The brutal depopulation of the Banda Islands ushered in vast demographic transformation. The Dutch established nutmeg plantations worked by enslaved people shipped from across coastal markets, from the Gujarat and Malabar coasts of India to Java, Borneo, and Sulawesi.6 Today, most of the islands' approximately 14,000 inhabitants are descendants of these displaced communities.

Seeds of Survival

Nutmeg cultivation remains central to life in the Banda islands. Most families tend to small nutmeg and clove farms alongside fishing for tuna, maintaining their connections to both land and sea. After gaining independence, the modern Indonesian state took control of the plantations until 1982, when they were redistributed to Bandanese villagers, finally returning the islands’ most precious resource to local hands.

Inevitably, most writing about the Banda islands’ role in history will draw the same tired comparison with its unlikely twin, Manhattan—one a global financial capital, the other a forgotten backwater. The smug subtext is always clear: look how history chose its winners and losers. But such comparisons miss the profoundly radical significance of Bandanese survival. Despite centuries of erasure, Bandanese villagers still maintain their ancestral practices, cultivating land and worshipping matter as living spirits embodied in plants, animals, rocks, water.

It’s this very logic that enabled the near-total destruction of the Bandas and its people—the mechanistic view that land is only worth its contribution to capital. European settlers justified their genocidal project by training themselves to see land as inanimate, valued only for its utility, disconnected from spiritual meaning, heritage, and survival.

I keep returning to these histories because they reveal something profound about how we've been taught to forget. It's no accident that we can casually sprinkle nutmeg in our holiday eggnog without thinking about the Bandas. This disconnection has been carefully constructed, a deliberate invisibility that makes it easier to treat both land and people as infinitely replaceable parts in a global supply chain.

But there is power in memory and in choice. What if, this holiday season, each time we reached for a jar of spices, we allowed ourselves to feel the weight of these connections—not to assuage guilt, but to recover something essential about how we relate to food, to land, to each other? The Bandanese aren't relics of history; they're active participants in building sustainable lives. Their survival isn't just about persistence against tragedy; it’s a reminder of interconnected practices that offer vital lessons for our collective future.

Ellen Roy. On the Edge of the Banda Zone: Past and Present in the Social Organization of a Moluccan Trading Network. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawai'i Press (2003) p. 2.

Villiers, John. “Trade and Society in the Banda Islands in the Sixteenth Century.” Modern Asian Studies 15, no. 4 (1981): p. 733.

Milton, Giles. Nathaniel's nutmeg : how one man's courage changed the course of history. London: Sceptre, 2000.

Loth, Vincent. Pioneers and Perkeniers: The Banda Islands in the 17th Century. Cakalele, vol. 6 (1995): 13-35.

Ghosh, Amitav, The Nutmeg's Curse: Parables for a Planet in Crisis. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2021.

Loth, p. 25.

SO important that these histories not only get told, but get told in this way. While I've long had a culinary appreciation for the spice, you have given me a whole new dimension to it. Such a powerful, beatiful call to actively and purposefully remember. Thank you, so much.