bones and all

notes on shame, cultural extraction, and learning to eat without apology

I lock eyes with a salmon head that dwarfs my outstretched palm. Severed and shrink-wrapped, it gapes back at me from the refrigerated section as I consider its price: $3.99 a pound.

I’ve cooked plenty of whole fish before, but never a head as large as my own. I glance over at the row of $12.99 fillets—pink flesh wet and eager, my usual fast pass to dinner in twenty. But lately, inflation has pushed me away from the farmer’s markets and prime cuts towards the margins: the necks, knucklebones and tendons found in Asian groceries and Latino bodegas that take slow, tender attention before yielding to our tongues.

They say if someone cooks fish head for you, it means they really love you. I don’t remember who “they” are, but it’s a tedious labour of love, sifting flesh from bone, cartilage and vertebrae. In Bengal, it’s a secret treat set aside for daughters and sisters after serving men their thick belly cuts. In my teenage years, when my brother left for college and my father traveled for work, my mother often made kanta bhaja for the two of us, a dry fry of buttery pomfret head in mustard oil and caramelised onions, garlic, and green chillies that literally means “fried bones”.

At home, I split the head apart with a heavy Japanese knife. The halves crack open like a geode, revealing chambers of apricot flesh and pearlescent jawbone. I salt both sides and roast them eyes-up in the oven, listening to the skin bubble as it tightens across the skull. The kitchen fills with the smell of the sea—briny and metallic, like low tide made of copper pennies.

*

I’ve never been squeamish about eating animals. My comfort with carnage was earned young, watching my mother chase crabs with a cleaver, helping her pluck shrimp guts with small fingers in exchange for the best treat: their heads, fried fresh and crunchy.

I spent winters in Kolkata going to the wet market with my grandmother, dodging bloody streams and flying guts in search of the day’s fresh catch. Thamama was a decades-long regular at the bajar; she knew everyone by name and which stalls had the best fare. Terrifying to everyone except her only granddaughter, she would bark orders at the maachwallas as they sliced scales and tails through their huge curved bonti. The air was perpetually thick with the tang of fresh blood on concrete, and I was forbidden from petting the stray cats and dogs that wove between our ankles, snouts focused on the scraps and entrails dripping off the table.

Once she’d filled her weathered jute bag, we’d pile into Thamama’s rattling white Ambassador for the chaotic ride home, windows down. My favourite memory of her is the day she bought a freshly slaughtered chicken, its headless corpse sliding wetly up and down the back seat with every swerve, my brother and cousin frantically flattening themselves against the doors to escape its slippery path as Thamama and I chuckled together with glee.

*

Where I come from, we eat everything down to the marrow. At least once a week, my mother makes mangshor jhol, a simple Bengali curry of goat and potatoes in a thin, spiced broth. But the real treasure lies inside the bones: some are hollow tubes that you tap tock tock and suck dry like a straw—these are reserved for my father. The knucklebones require more time and teeth to tear off the cartilage and pry out the buttery marrow within. Those are for my mother and me to gnaw on while my father finishes his meal: two bitches with a bone.

When I first came to the U.S. for college, I was struck by how rare it was to find meat on the bone. Instead: chicken breasts, tilapia fillets, ground beef formed into perfect discs. Meat stripped of its context, turned into borderless blotches of flesh—flabby and flapping, untethered from the body that once held them, drifting like clouds across supermarket shelves and cafeteria trays.

At my little Midwestern school, Fourth Meal was a beloved tradition. Every night after 10pm, one of the cafeterias served late night comfort foods. Thursday was Wing Night, a thick crowd clamouring over buffalo or barbecue. I clearly remember my first Wing Night, not for the pounding pop hits or the sticky fingers, but for my astonishment at how much meat my new friends left clinging to their wing bones. I was eighteen and new to this country, still learning the choreography of American friendship and which hungers were acceptable to display. I had to restrain myself from snatching those meaty joints from their plates and stripping them clean.

(I still feel this urge whenever I eat chicken with friends—the impulse to scrape off every sinew, to notch the drumstick against my teeth and flick off its cartilage cap. Instead, it’s an indulgence I reserve for my kitchen, for quiet afternoons alone making stock when the chondral crunch won’t announce my foreignness to anyone but the walls.)

*

I’ve spent years perfecting this performance of restraint, learning to signal my assimilation by leaving good meat on bones. The impulse to eat with my fingers, to suck marrow through my teeth, has never disappeared—I’ve just gotten better at suppressing it in public.

For my birthday this year, my parents took me to a steakhouse in Chicago. We were all dressed to the nines, my mother and I both in new shoes we’d bought that afternoon. The restaurant was all mahogany walls and brass fittings, encyclopedic wine lists and forty dollar truffle shavings—a temple to the transformation of appetite into performance.

We ordered a ribeye steak served on the bone to share. I watched my mother’s fingers dance past the bleeding meat to pluck the rib off the plate. She held it between her fingers like a communion wafer, working her teeth along its ridges, extracting every last sinew and marrow with the focused intensity of someone who understands that waste is sin.

Watching her, I felt that same feeling I’d felt on my first Wing Night at college—a protective urgency that rose up in my chest like smoke, an impulse to shield her from judgment. But this time the feeling was more confused, tinged with envy at her unselfconscious pleasure, her indifference to the polite theater I’d been carefully observing since I first arrived in the U.S. Of all the subversive practices I’ve learned since, I never imagined eating bones could be one of them.

*

This is the peculiar geography of shame—how it maps itself onto the most basic acts of survival. I’ve learned to eat around the edges of my appetites, to perform a culturally acceptable version of refinement that keeps my hungers hidden. But good bones have a way of finding their path to respectability, made desirable through newfound sophistication.

In April, my friend Isa and I celebrated her birthday at a Mexican restaurant in Sedona, AZ. We ordered lamb colorado, enchiladas, and roasted bone marrow. The marrow arrived in its bone like a canoe in a sea of elote and spoons for paddles. It reminded me of a bamboo trunk sliced open, like the ones my classmates and I used to carry water and steam rice in a middle school jungle survival course. As I spooned out the marrow, I imagined the bone bisected by a machete, halves toppling apart like firewood.

For weeks afterward, I couldn’t stop noticing the appearance of animal bones in fine dining settings, elevated through the aesthetic of capital. The transformation has been systematic and swift: here in Chicago, bone marrow began gracing the menus of prominent restaurants in the early 2000s; by 2012, Newsweek had declared it “the food industry’s latest fad”. Articles mentioning how Bourdain chose “roast bone marrow with parsley and caper salad, with a few toasted slices of baguette and some good sea salt” as his last meal on earth circulated widely before and after his untimely death in 2018.

It’s always jarring to find these vectors of desperation transformed into destination dining. When foods born of economic necessity get repackaged as artisanal experience, they become inaccessible to the very communities that rely on their balance of flavour and affordability for survival. Newly minted as symbols of virtue—whether nutritional, environmental, or political—the people who never had a choice in eating them are priced out of their own sustenance.

*

An hour later, I know the salmon head is cooked by looking into its eyes. It’s a trick I learned from a Sicilian roommate: the first time we cooked a snapper together, she took it out halfway through and pointed at the eyes, still translucent and bright. “Is still alive,” she announced sagely in her thick accent as she rotated the tray back into the oven (which she pronounced “hooven”) to continue cooking until its gaze grew cloudy.

In the many parts of Asia where I grew up, fish head curry is a delicacy and the eye is often the most prized part. In Singapore, the eye’s gelatinous texture and rich, fatty flavour is set aside as a special treat for guests. It’s my friend Lydia’s favourite part of a fish, along with the cheek—a dense but tender little pocket cupping the eye like a hammock. I think of her every time I scoop it out.

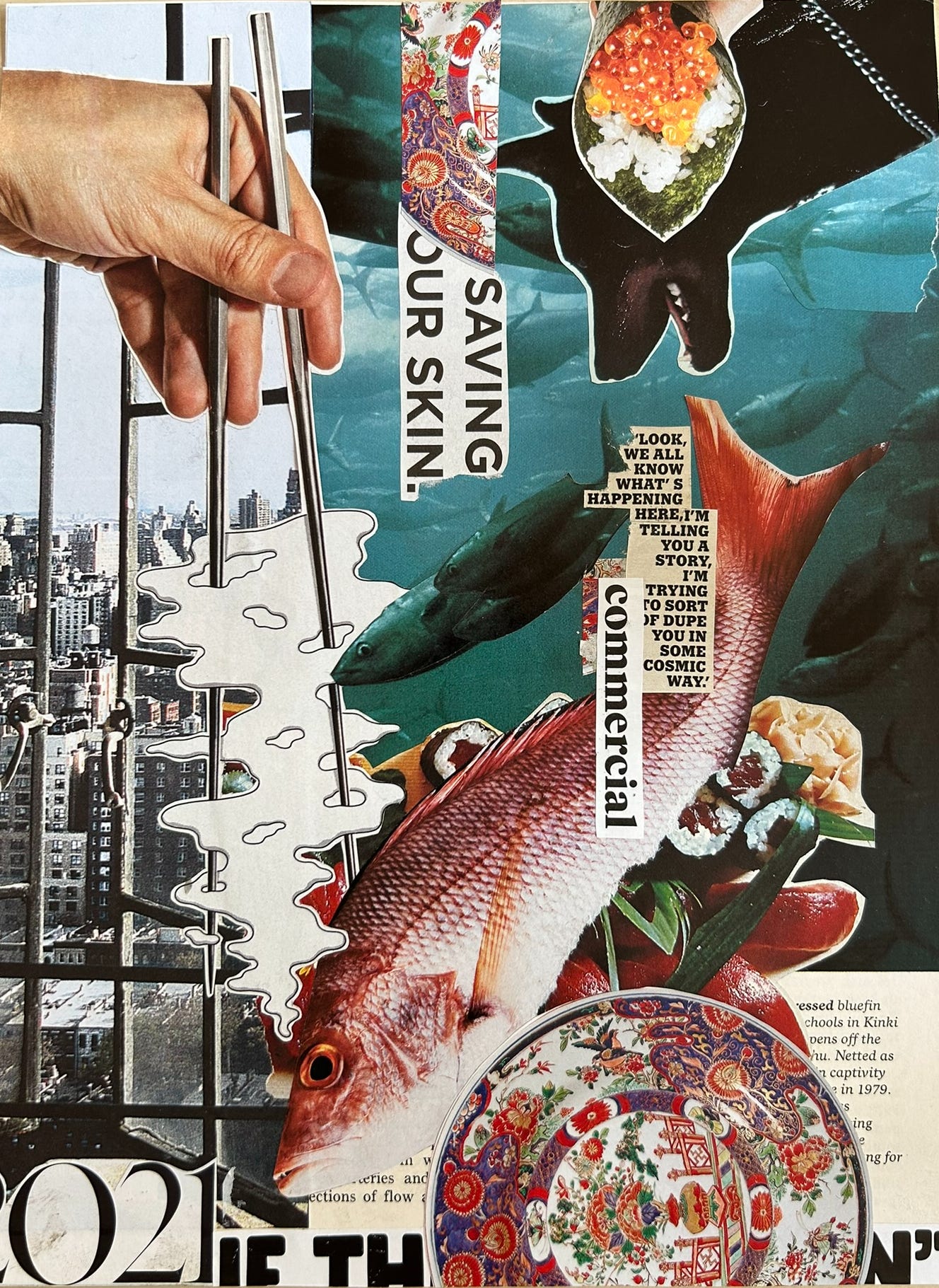

In the US, fish heads remain largely the province of immigrant communities; high-end restaurants tend to stick to simpler, boneless cuts that avoid eye contact, keeping the prices of lesser cuts and whole fish low. Until, of course, the right restaurant decides to rebrand refuse, newly sanctified by the language of “nose-to-tail”. A Guardian recipe inspired by fish head tacos at Noma, the acclaimed Copenhagen restaurant where dinner with a wine pairing could run you up to $800, begins with this line: “Like many foods that we think of as rubbish, fish heads are seen as a delicacy in many other countries.”

What a generous way to introduce readers to centuries of culinary tradition—by first assuring them it's trash. I wonder if the Guardian would introduce a recipe for foie gras by noting that “like many traditions we think of as torture, this is considered fancy in France.”

*

I pick the head apart slowly, beginning with the cheek. I eat it the way my friend and former roommate Monica taught me: first a dollop of ssamjang spread thick on seasoned seaweed, followed by a layer of rice, a morsel of fish, kimchi for acidity, and perilla leaf for brightness.

It’s strange, the way I can go on with anecdotes about eating the unlovely parts of animals and how they connect me to the people and places that have shaped me, all while feeling unable to own this heritage outside the safe anonymity of my kitchen. Even now, I feel a resistance to share this. When I told my mother about writing this essay, she laughed nervously and said, “please don’t.” (Sorry, Ma.)

There it is again: the shame. But now, I see it’s grown into something else: shame at the way I’ve learned to police myself at the tables of others, to perform “refinement” at the expense of my own familiar traditions and heritage. Beneath the shame, anger—at how long it took me to see the machine at work, at witnessing extraction in its most intimate form: teaching people to be ashamed of their own survival, then selling it back to them as culture.

So this is what colonisation looks like at the dinner table: the slow erosion of instinct, the careful unlearning of taboo pleasure, and the transformation of that erasure into profit. Food becomes a site of performance, a test designed for failure.

Perhaps the deepest act of resistance isn't learning to eat politely. Perhaps it's refusing to perform at all. To understand that the systems policing our pleasure are the same ones repackaging it for profit.

To stop asking permission to be hungry and start trusting that our appetites are valid exactly as they are. Bones and all.

"Bones and all"!!! Thank you for this piece.

I noticed just the other day that I’d not seen anything from you for a while. I was very pleased to see this come into my email.

Yes, eating and being without shame is absolutely needed. I really appreciated your mother’s enjoyment of the whole steak. I mean, if we’re going to take life then we might want to actually appreciate all of it. I grew up eating things that were available to my working poor family of African decedent in the southern US. The only thing I don’t eat now is pig intestines. Everything else is absolutely in my diet. Eating in for oxtails now (amazing how expensive they are these days, I’m sure my mom never paid these prices). Great writing.