rediscovering long pepper

the rise, fall, and enduring connections of an obscure ingredient forgotten by time and trade.

Note: I’m presenting this as the first essay in my monthly series about spices, but in truth it’s my second. If you missed my piece about mahleb and its connections to Armenian diasporic identity, you can find it here at From the Desk of Alicia Kennedy.

It’s November 2022. I’m in a parking lot in Bali plotting a last-minute expedition to source spices.

When the idea of this newsletter first came to me in 2021, this was the dream: to be wandering the fields and forests where spices grow, talking to farmers, witnessing the life cycle of an ingredient from earth to hearth. I always imagined I’d start here in Indonesia, the native home of so many spices, where I could speak the language and zip around on motorbike and feel connected to this land of abundance that had raised me, too.

As always with dreams, reality was a different story. I had five days, but two had been spent chasing down empty leads and a third washed out by rain. Should I drive two hours north looking for clove fields or spend the day talking to the women at the local market? I flipped between the map and my notes, anxious and indecisive, feeling every hour pass by more urgently than the last.

I looked up from my phone and caught on a creeping vine dotted with gnarled little fingers of lime-green and orange-red fruits. Heart-shaped leaves twined gracefully along the chain link fence separating my motorbike from the next house.

I remembered a conversation with Indonesian chef and author Petty Elliott, who had told me about a conical fruit known as long pepper or cabe jawa (cha-bay ja-wah, meaning Javanese pepper). Javanese cooks once ground it with ginger and black pepper to make a piquant paste not unlike sambal, Indonesia’s iconic chilli paste, long before chillies existed in the archipelago.

At the time, I’d only ever encountered these peppers in their sundried form, which resemble small, spiny reeds. They’re floral and hot when broken and ground, but I couldn’t imagine these brittle pods as a substitute for the vibrant sambals I’d grown up eating.

“Normally it’s dried,” Elliott agreed; these can be found in specialty stores and high end spice suppliers. “But the fresh one, when it’s ripe, you grind it with a pestle and mortar [to make sambal],” she explained. “The first time I tried it, oh my gosh. It’s really like chilli, the flavour and texture, because it’s soft and red.”

I looked again at the stubbly fruits vining peacefully along the fence. Against my better judgement and my mother’s warning voice in my head, I plucked a few peppers and gingerly took a bite. At first, it was sharp and spicy like ginger, hotter than black pepper but without the searing fire of a fresh hot chilli. It had a sweet smokiness like nutmeg or cardamom, along with green vegetal notes and a cooling citrus finish.

I was so surprised by the complex heat of this roadside botanical. Despite my research and conversation with Elliott, I hardly knew anything about long pepper. It hadn’t even made it onto my list of spices to track down on my Bali trip. And yet, out of all the ingredients I carted back home, this one haunted me the most. Why did I know so little about this strange pepper, long-forgotten by time and trade?

*

For nearly two thousand years before chillies, there was long pepper.

A cousin of our household stalwart Piper nigrum, long pepper was one of the most valuable exports of the ancient world. The Indian Piper longum and its Indonesian twin, piper retrofactum, both grow easily and abundantly in their indigenous tropical habitats, creeping around trees and fences on slender flowering vines.

Known by the Sanskrit name pippali in India, long pepper is referenced in ancient Ayurvedic texts dated between 1200 and 900 BCE. Prized for kindling agni (digestive fire), long pepper is used to stimulate digestion, detoxify the body, and soothe the respiratory tract. In Ayurvedic medicinal traditions, long pepper is combined with black pepper and ginger to form trikatu, meaning “three pungents”, to support digestion by “nurturing the fire in the belly”.

Long and black pepper are both native to India; long pepper grows in the subcontinent’s northern regions, whereas black pepper is indigenous to India’s southern coast. With its proximity to the desert caravan routes linking Asia and the Arabian Peninsula to the Mediterranean coast, long pepper was the first to travel overland, arriving in Greece as early as the 6th century BCE. Peppercorns followed later with the expansion of maritime trade between Europe and Asia at the beginning of the common era.

Long or short, black or white, pepper commanded high prices in ancient Mediterranean markets. In Naturalis Historia (Natural History), completed in 77 CE, Roman encyclopedist Pliny the Elder recorded the following prices: “Long pepper is sold at 15 denarii a pound, white pepper at 7, and black at 4.” At the time, one pound of long pepper would have been equivalent to the monthly salary of a secretary or lecturer.

Naturally, as the most expensive and aggressively pungent spice available at the time, pepper became a symbol of power and virility in ancient Rome, and a luxury ingredient for tonics to cure impotence. Elite families used pepper liberally in their food as a demonstration of wealth, from flavouring wine to seasoning fish and meat.

Spicy ingredients like mustard and horseradish have been cultivated in the Mediterranean basin since antiquity. But piperine, the alkaloid shared by both black and long pepper, activates the body’s heat- and pain-sensing receptors, causing the thrilling (or for some, wholly unpleasant) burning sensation that comes from eating spicy food. It’s likely that long pepper was the first exposure to the kind of heat that makes spicy food so addictive.

Pliny did not appreciate the impact of this addiction on imperial coffers, to the tune of 50 million sesterces in annual trade deficits. In Naturalis Historia, he writes, “Why do we like it so much? Some foods attract by sweetness, some by their appearance, but neither the pod nor the berry of pepper has anything to be said for it. We only want it for its bite – and we will go to India to get it. Who was the first to try it with food? Who was so anxious to develop an appetite that hunger would not do the trick?”

Perhaps it is human to seek out danger. Perhaps, like us, our ancient forebears sought out the rush of adrenaline that floods our bodies in response to the burning pain of spice. Hearts racing, tongues smouldering, eyes and nose and pores seeping, we feel alive and revel in the primal knowledge that we are (probably) safe.

*

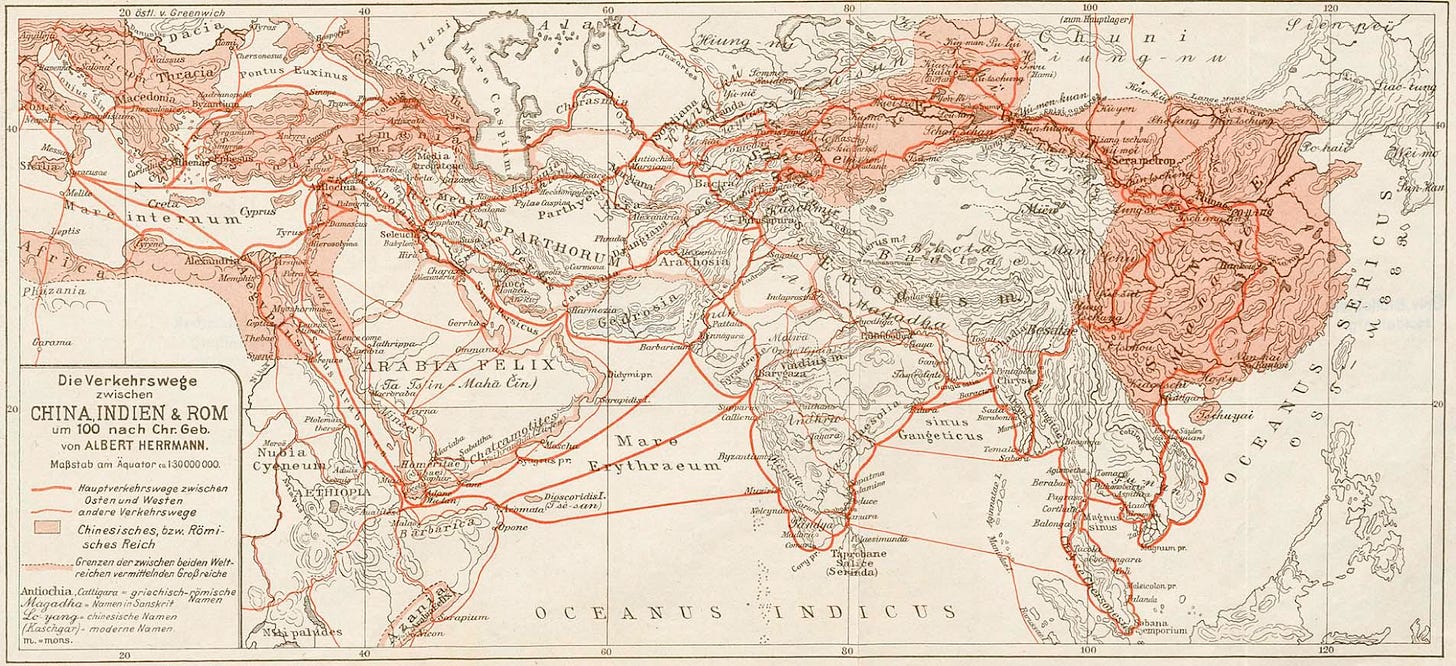

For over two millennia before the common era, Arab traders monopolised the caravan trade between Asia and the Mediterranean, closely guarding their sources and driving up prices for spices like long pepper. But when Rome annexed Egypt in 30 BCE, Roman ships gained direct access to India via the Red Sea, bypassing the ancient Arab trade network by establishing new maritime routes from Rome to Alexandria.

Each summer, a fleet of Roman merchant ships set out from the banks of the Nile on a hundred-day journey, first down the Red Sea corridor along the African coast, before crossing the Arabian Sea on eastern monsoon winds to reach India’s Malabar coast, where black pepper grows wild. This pathway, documented in sources like the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, would remain a primary link between Asia and Europe for another millennium, until the fall of Rome.

Although long pepper remained a significant export in Europe through the Middle Ages, the opening of the maritime route likely spelled the beginning of the end. While the seas always carried their share of risk—storms and pirates and sirens and scurvy—the overland route was longer and required paying heavy tariffs along the way. With a shorter, more direct distance to travel, black pepper became more widely available and affordable.

The arrival of chillies, though, seems to have been the true nail in the coffin. The peppers of the New World were spicier and stored better, retaining more of their flavour when dried. Where long pepper is difficult to grow and takes up to four years to bear fruits, chilli plants take just twelve weeks to produce fruits. An unfussy crop happily suited to most environments, chillies quickly took root in the soil and the senses, becoming an essential component in countless cuisines across the world.

Within a century, chillies went forth and multiplied, reaching Hungary (paprika), West Africa (scotch bonnet), and Korea (gochugaru), to name a select few among the untold thousands of chilli descendants now scattered throughout the world. Meanwhile, long pepper faded into culinary and historical obscurity.

How banal and tragic, to be replaced so quickly by your brighter, hotter, more pliable cousin.

*

So why should we care about this arcane little pepper?

I know I’m biased, but I’m fascinated by long pepper as one of the earliest luxury goods connecting ancient empires. Its rise and eventual descent into obscurity reveals how trade and power control what becomes visible and ordinary—and conversely, what remains invisible and exotic.

When I first started reading about spices, I had assumed that Europeans didn’t reach Asia until the sixteenth century due to the tight hold Arab traders had as middlemen navigating the unknown world beyond Mediterranean waters. Most accounts of the European spice trade with Asia begin with the Portuguese navigator Vasco da Gama’s 1497 voyage to India. But the story of long pepper reveals how contact between Europe and Asia existed millennia before da Gama’s fateful trip around the Cape of Good Hope.

Learning about long pepper also makes me wonder how India existed in the ancient Mediterranean imagination. What was it like for the Romans to arrive at the cosmopolitan port city of Muziris on the Malabar coast? Long since lost to the floods, Muziris was where merchants from across India, Arabia, and China once gathered to trade goods from far-flung corners: Indian ivory, Persian turquoise, Chinese silk, Sri Lankan rubies, Sumatran gold, Bandanese nutmeg. I wonder what tales the Romans brought back about this balmy crossroads, thick with rain, where Jews and Christians and Phoenicians and Arabs lived alongside each other, cobbling together new languages and cultures of exchange.

To me, the early movements of ingredients like long pepper are the best demonstration of how cuisine has always, always been cross-cultural. When we forget about these ingredients, we lose our conception of millennia-old connections between cultures like India and Italy upon which the modern global trade system is built. Stories like this give lie to the borders and ideologies that separate us when there is, in truth, so much more that connects us.

This essay is the first of many to explore the themes I’m most interested in unpacking: the deep, complex stories about spices, how they connect us across impossibly long distances and ages, and how these connections have laid the foundation for our modern global systems. There are so many more to uncover, and I look forward to sharing them with you in the coming months.

Which spices are you excited to learn more about? Share with me in the comments!

Love the idea of learning about juniper berries! Beautiful writing, eagerly await the next piece 😊

I’m interested in turmeric and coriander seed. I have been interested in studying how food has travelled across the world due to imperialism and diaspora. Thank you for writing this piece and sharing it! I hope we can build stronger cross-cultural relationships and empathy through understanding why we eat what we eat!